Magic in abundance

By Sergio Ariza

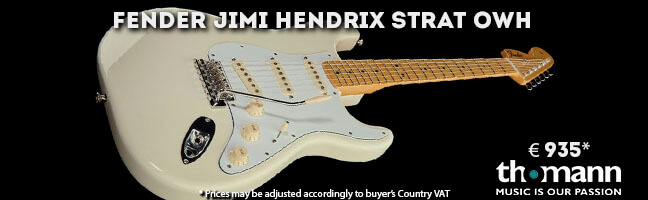

Al Kooper had jammed with Moby Grape in early 1968 and it had been especially productive, so he decided to do more like the jazz musicians and rent a studio for a couple of days and record an album based on jams. But who were the best musicians Kooper knew? Basically he knew them all, as up to that moment he had played with Dylan, the Who, had been part of the Blues Project and had just led the first album of Blood, Sweat & Tears, Child Is Father To The Man. As if that wasn't enough, on April 18th 1968 he had helped record Hendrix's Electric Ladyland, by playing the piano on Long Hot Summer Night. Hendrix had been so delighted with him that he had given him one of his Stratocasters.

But of all the rock legends, the guy who had impressed Kooper most was the guitarist who played with him in the original recording of Dylan's immortal Like A Rolling Stone three years earlier, Mike Bloomfield. Bloomfield had just released the first Electric Flag album, with the group he had founded in 1967 and which had been one of the stars of the Monterey festival. However the fact is that Bloomfield’s serious problems with insomnia, coupled with his heroin addiction, had meant that the leadership of his band had to be passed to the drummer Buddy Miles. Despite the fact that A Long Time Comin' was very well received by both the public and critics (Miles Davis himself was known for his admiration for Over Loving You), Bloomfield was all over the place, with his ghosts haunting him, when he received a call from his friend Kooper.

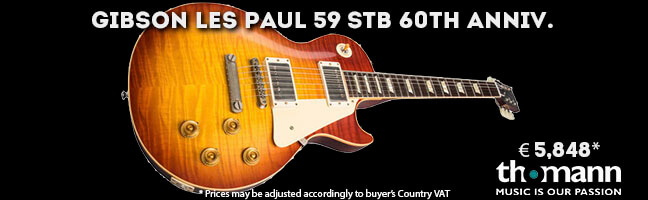

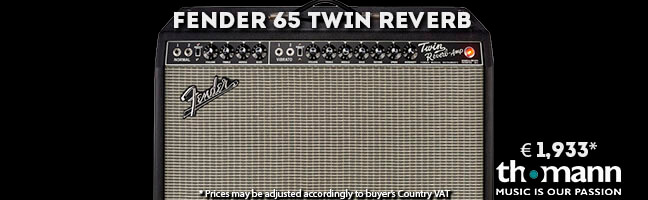

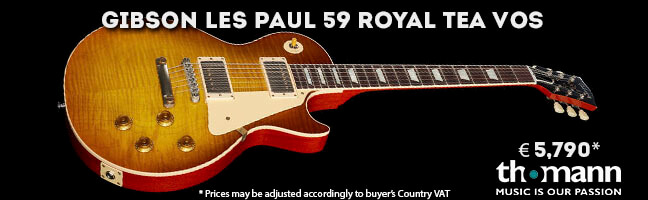

Bloomfield thought Kooper’s proposal was a good idea and so took along part of his band to the session: with Barry Goldberg on piano and Harvey Brooks on bass, while the drums would be played by Eddie Hoh, an experienced session drummer, and friend of Kooper, who had played with The Mamas & The Papas, Donovan, Gene Clark, Tim Buckley and the Monkees. On May 28th everyone was ready, Bloomfield showed up with his Gibson Les Paul Standard Sunburst from 59 and a Twin Reverb, and as he plugged it in those around him could see that it was going to be one of his good days. The magic began to flow in the session with three long instrumental pieces composed between Bloomfield and Kooper, and a cover version, also instrumental, of Jerry Ragovoy and Mort Shuman's Stop, plus a cover version of Curtis Mayfield's Man's Temptation with Kooper taking the lead vocal for the only time in the whole evening.

The session opened with Albert's Shuffle, a track in which the guitarist shines with a fierce intensity that distinguishes him from orthodox blues. Then comes Stop and, incredibly, things get better, as Bloomfield’s first solo is the best presentation of his peculiar style, in which you can see that he is drawing on the best, like B.B. and Albert King; but he is able to define his own sound and not be a mere imitator. On the second solo, starting from the third minute, he allows himself several pure soul licks, doing his best Mayfield reinterpretation, which is capable of raising the hairs on the back of your neck.

His Holy Modal Majesty is a tribute to John Coltrane where Bloomfield once again recovers the best essence of his East West, showing the tremendous influence his style had on people like the Allman Brothers, and being the closest moment to the spirit of the album, of improvisation that is close to jazz. The first side closes with another great blues track, Really, in which it is proven that Bloomfield is blessed by the Gods and has that which the gypsies call ‘duende’.

But the incredible thing is that, following this great performance, Bloomfield was not able to master his demons and the next day he didn't even show up to complete the record, leaving Kooper with the responsibility of finding a last-minute replacement. The one good thing is, if you're Al Kooper, your address book has names in it like Stephen Stills. The leader of Buffalo Springfield had just left his band and had nothing better to do, so he joined the session to complete a totally different, yet very enjoyable, ‘B side’ to the album.

Instead of 'jams', it was decided to draw on songs that everyone liked so they could do their own version, so they did: It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry by Dylan, a song whose original version had Brooks and Bloomfield as session players; Season of the Witch by Donovan, a song whose original version had Hoh as a drummer; You Don't Love Me by Willie Cobbs; and an original song by Brooks called Harvey's Tune. Of the entire batch the most outstanding was the long version of Season of the Witch with a great Stills using the wah wah splendidly (possibly with his White Falcon), proving that his jams with Hendrix had taught him a secret or two from the great wizard.

The album was released on July 22nd and became an unexpected success, rising to number 12, and remaining in the charts for several months. Not bad for an album that had cost just a few thousand dollars to make. Kooper ended up forgiving Bloomfield and they played together several nights in a row at the Fillmore West. But Bloomfield left again on the last day. He was tired of the success and the concept of 'supergroup' that had been assigned to the album.

The one who would take note would be Stephen Stills who, the same day that this album was released, would join David Crosby of the Byrds and Graham Nash of the Hollies, to form one of the first, and most successful, supergroups in the history of rock, Crosby, Stills & Nash, who would be joined shortly thereafter by Neil Young.

Bloomfield had one year left of his career until the heroin and his head almost completely blew him away. Bloomfield was not there when bands like C,S, N & Y, Allman and Blind Faith drew on his spirit to play in front of hundreds of thousands of people, but in the 29 minutes of the first side of this album he offered magic in abundance.