The Reverend of All the Keys

by Alberto D. Prieto

On

the outskirts of town, between the traffic lights and road signs, the neon

lights shine. Not everyone hears their call. And not everyone who hears the

call knows the secret. The road to paradise goes by way of winding roads, and

you have to know how to take your chances, understand the signs, get in the

car, slam it in gear and put the pedal to the metal. Give it the gas, gun the

engine, go over the top with the tone and burn some rubber. The

beautiful babe will raise her sunglasses, look at you and smile. The riff

rings out. To uncover all the secrets of the Glory you have to make a stop at the

La Grange brothel.

There

is one thing others don't have. And they’ll never have it, either. And that’s

the experience in the '60s of having combed your hair every morning, looking at

yourself in the mirror and singing into the hair brush you're holding in both

hands. To be a teenager in that era, to wake up every morning and, after taking

the shower, pop your zits to the rhythm of Elvis and Chuck Berry,

to be among those who trimmed their first beard in an imitation of the careless

flair of Hendrix... it's not the same thing to be born into one era as another.

That's why you have to acknowledge the immense good fortune that Billy

Gibbons; a native Texan born in Houston, in 1949, had simply

by living his rebellious age at a time when the gods were preaching their

catechisms.

Billy

Gibbons listened

to the sermons of the great and the good at that precise moment in time when

the mind is eager for signs, ready to explore new roads, open to revelations

and to becoming part of Something. To be the disciple, vinyl record in

hand, of the people who have confirmed our faith over the last six decades, effectively

paved the way for our Billy to becoming one of the true pillars shaping the

expansion of this six string religion. His generation had another advantage too:

the explosion of mass audiovisual culture. We are of course referring to the TV. Billy Gibbons learned his

craft at the frets of the masters but he was a pioneer of the cathode ray tube ministry

too. Through preaching and skillfully applying the incipient marketing

techniques of the day, he made off with the keys to the second secret: not being

the most handsome of men (at least when he was young because 40 years hence who

the hell knows?), chubby and more earthy than the sunbaked land of Texas,

he had, and has, found eternal life dangling from a keychain on his worn blue

jeans.

He

figured out the first one as a teenager the moment he began to pluck and strum

his first Gibson Melody Maker. That was where little Billy found

that part of the road that was already travelled. A Christmas present shortly

after he turned 14, the simple wonder of which would later become his fetish

model came accompanied by a small Fender Champ amp. With these two items

he began to repeat the psalms of John Lee Hooker, and the parables of Muddy

Waters. Over five decades later, Gibbons hasn't lost any of the hundreds

of pieces he learned. He conserves each and every one of the keys he used to

cross every threshold, including that relic he gave to a friend as a present

years ago, and came back into his hands two decades later. Are these

coincidences? Or a sign?

His

elders, the generation immediately before him, had blown out the dust of

sanctimonious mothballs, mites spreading chaotically through the air, with no

one with the faintest idea as to where they would land. But it was obvious that

all the kids on the other end of their transistor radios, were joyfully

breathing it all in while causing an allergic reaction amongst all their

parents. What could be better than that for a teenager?

Maybe

opening the show for your idol, perhaps. That was something that happened five

years after he first plugged in that marvelous Melody Maker with one single

coil pickup, feeding his ambition as he went. It was in 1968, when Gibbons

was the leader and guitarist of a band working the Texas club circuit, The

Moving Sidewalks, a psychedelic blues rock quartet that didn't last

long and released just a few records. But if the finest fragrances are

contained in small bottles, the limited legacy of this combo yielded one

byproduct so aromatic that no one could top it.

The

burgeoning Jimi Hendrix Experience was touring the United States and

the Sidewalks opened several of their shows. Hendrix was already giving

notice of his eternal reign over the six strings and soon afterwards he

revealed on Dick Cavett’s show on ABC that he had been impressed

by Gibbons' guitar playing skills. That this Texan had all the keys and

would be the next to take care of business with the guitar… And his

statements in that sense anointed him as the Reverend chosen by the blues

rock messiah himself.

The

Sidewalks didn’t make the leap to the national circuit, but their soul

of the six strings did. At the controls of a pink Stratocaster that Hendrix

saved from the fire —"It's too beautiful, you keep it, Billy",

said Jimi when he handed it over to him —, Gibbons put together a

classic Texas power trio to show off his passport as a genius of the

scales, now that he could show his visa from the eternal king of the instrument

to the public at large.

He

picked a drummer, Frank Beard, who in turn recommended a bassist he had

played with in The American Blues by the name of Dusty Hill. The

cocktail blended from the start and, almost before they got around to putting

out a single record, the gigs just kept coming until it resembled something

like a three year tour all over the country. ZZ Top had drunk from the

purest of sources and their interpretation of the blues, baked by the Texas

sun and the raw tone of their live sound, opened up all the locks.

That

was how Billy found the third secret in the legacy of his elders:

already a six-string prodigy and a precocious visionary of telemarketing, the

third key lay in recognizing that the dikes of political correctness had finally

come tumbling down and that now you didn't have to just sing love songs, you could

do odes to cars, beer and hookers too, and that

realization turned him, as leader of ZZ Top, into the perfect disciple for

showing the masses the path to glory.

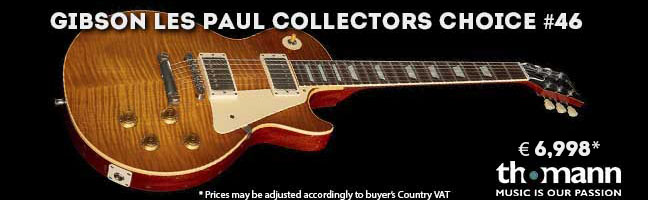

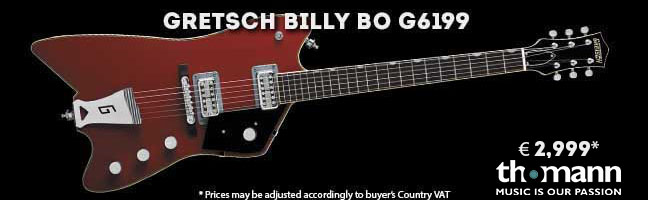

The

passion of Billy for guitars is directly proportional to his concept of showbiz

performance. Over the years, ZZ Top has known how to blend all kinds of topics

into one with flair and irreverence: chicks, cars and guitars —not necessarily

in that order— was the basic combination. Embellished with the appropriate wry

sidelong glances for each era: from the grittiest to the sophisticated, by way

of synthesizers and even electronic drums, they would set the trend each

time. The combo named their albums in Spanish from the beginning of their

career —five of seven during their first decade, the '70s—, but not now

with Latino music prevailing in the US and his native Texas. Gibbons

uses gel picks that light up in the dark; covers the straps of his belt with

old cigarette packs; plays fur-covered instruments and does hilarious dance

routines in tandem with Hill onstage; buys every guitar he finds at all

interesting on the spot and doesn't care how many instruments he's already

accumulated —"the best ones are still out there, dude"—; he champions

the luthier industry by exhibiting crazy designs by the likes of John

Bolin and other geniuses of putting hand to wood. But above all he

customizes guitars to his taste, hollowing out the bodies, making the necks

lighter, stringing them with light gauge materials —his thick tone is part of

his prodigious technique—, and then plays them as just another element of the

show. It doesn't matter if it's a Les Paul, a Telecaster, a Gretsch

Thunderbird or a one-of-a-kind instrument. Everything is susceptible to

being picked up to meet the whims of the bearded virtuoso holding it because

he's the one, and the only one, who knows what he wants.

The

story of this trio, which has now racked up 45 years of onstage performances,

is one of self-sufficient pals who are well aware of a uniqueness that is

chosen and not imposed. From their early days together, they decided to hold on

to the keys to their studio, limit access to executing their projects, and

avoid inviting guest musicians or collaborating with them. They consciously

adhered to a pure American sound, a white blues of the ranch and saloon marked

by aggressive music and lyrics that get personal without slipping into the

obscene.

Incidentally,

they opted to let their long beards of St. Peter grow before they

had even reached thirty, hide their eyes behind dark sunglasses, and anticipated

going bald with the help of ridiculous hats. What all that achieved is that now

they can never again get any older, an eternal life that, in rock 'n' roll,

is normally reserved for the legends that die before their time. And they have created

a trademark image for themselves that opened the gates to heaven on earth. They

climbed into a convertible of glory

— that goes even beyond the fame—, and made themselves as recognizable

the world over as the Marlboro Man, used Mustangs or the neon

lights of Las Vegas.

Billy says his first words were “Ford,

Chevrolet and Cadillac… that's what my mother claims”. The thing is that Gibbons,

Hill and Beard —strangely, the only one who never let his beard

grow—began the posing long before they would invent the term, producing video

clips with ridiculous, choreographed routines that made completely fun of

themselves, making their presence felt with appearances in movies and TV

series, as guardians of the essential elements of the dream represented by an

American flag waving in the sleepy desert of Chihuahua. And the

guitar-based sound of their music somehow became the soundtrack of the American

way of life…

Because,

while they did succumb to the apathetic rigors of the '80s just like everyone

else, ZZ Top knew how to keep the secret safe and sound: the fat, aggressive

sound of Gibbons never fell away from their records, in spite of the fact

it would engage in dialogue with echoes, drum machines and

standard song structures of verse / verse / chorus / verse and a loooooooooong fade

out... Maybe that's what saved them.

Because

the blues had wanted to show the way to Billy since he was young,

he wore out the first needles on his turntable playing the stunning ‘Beano

Album’ by John Mayall and The Bluesbreakers (1966), a sort of rite-of-initiation

record, a Mecca anyone could make a pilgrimage to whenever they felt lost and

their soul was restless … Gibbons was spellbound by those 12 marvelous

tracks with under 38 minutes of music, with a superb Eric Clapton not

only holding a Beano comic book that gave the album its name

forever but on the back cover, the God of the Slow Hand was glimpsed playing

a Les Paul Sunburst with some Marshall amps decorating the room

in the background…

Billy, hearing the jingle jangle

of the signals, could understand that if he grabbed on to this revelation

forever, maybe he would be able to investigate the deepest roots of blues rock.

But he didn't, until another chance encounter sent by the maker of the divine

music and terrestrial temptations crossed his path.

Gibbons

couldn't

open the doors to his glory because he lacked the master key: a ‘59 Les Paul

Sunburst like Clapton's. But then a little bit of money came in from

California, when a beautiful girlfriend sent him the profits from

selling a 1936 Packard that Gibbons loaned her to go find fame

and fortune in Hollywood. The car brought the girl good luck and both of

them began to believe in some kind of divine connection —maybe she was such a

bad actress that she needed a miracle to score any kind of small role in the

movies— and the Packard was baptized as ‘Pearly Gates’, which is

what Americans called the doors to heaven…

When the money arrived back in Texas,

the owner of a Sunburst lost his head and accepted a deal to sell it for

250 dollars. He took it out of the trunk and gave it to someone who,

only a couple of years later, would unlock the blues with it in his

hand. It might be the worst sale of that model guitar in history and certainly

the worst business deal closed in a parking lot in 1968. If not for all

time.

All

those coincidences can't be coincidental. The guitar took the name of the car, Gibbons

plugged it into some Marshalls, repeated his mantra learned between

the grooves of the ‘Beano’ LP —”tone, tone, tone”— and began to

play, now for forever, with the distortion of the gain. He slipped his genius

through the opening in all the locks, figuring out the keys to each guitar that

fell into his hands. During these last four decades he earned the legendary

fame of the holder-owner of the secret, master of the keys, the doorman to blues

heaven.

So,

whether he plays a Gibson Melody Maker solid body just like the one in

his early days, drives a Fender Telecaster, plays long spiraling lines

on a Jazzmaster, or bows down for once to the eternal Stratocaster,

there is one thing the owner of the keys to the blues never forgets:

that you only get to paradise by driving through the desert of Chihuahua,

with a beautiful babe in the passenger seat of your car, and that you always

have to pay attention to the divine signs if you want to cross the threshold of

glory and enjoy eternal life in the seductive world of rock ’n’ roll.