The Most Important Guitarists of Bob Dylan’s Career

By Sergio Ariza

Today we want to pay tribute to possibly the most important figure in popular music of the 20th century, Bob Dylan. We will do so by concentrating on the most significant guitarists who played with him, mind you, putting together a short list proved almost impossible (almost all the big names have played with him) so we will focus on those who have left a bigger mark, and not just periodically, because otherwise the list would go on forever containing names such as Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Carlos Santana, Slash, Mick Ronson, Ronnie Wood, George Harrison and even Steve Jones from the Sex Pistols.

Bruce Langhorne

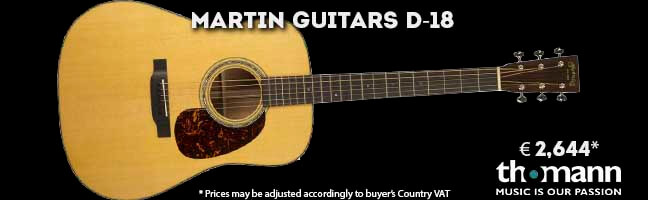

One of the most unknown, yet most important Dylan collaborators. Langhorne was an African-American guitarist who had become the main session musician on the Greenwich Village music scene, playing with names like Joan Baez, Richie Havens and The Clancy Brothers. In 1961 he was introduced to a young man who had just arrived to New York, after listening to him, Langhorne thought he was a joke, a terrible singer, but after listening to his songs his opinion completely changed. He was Dylan’s first electric guitarist, as in 1962, in full force on the recording of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, they cut Mixed Up Confusion, a song with the whole band where you can hear Langhorne’s 1920 Martin 1-21, the one he had added the extra pickup to, and plugged into a Fender Twin amp 3 years before his famous conversion to electric. That wasn’t the only contribution he made to Dylan’s career, the most important of which was what he did on Bringing it All Back Home, the first piece of the electric trilogy bt Dylan in the mid-60s, where he was the lead on numbers like Subterranean Homesick Blues, She Belongs to Me, Maggie’s Farm, Love Minus Zero, On The Road Again, Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream and Mr. Tambourine Man, a song where he not only provides the counterpoint to the melody with force, but also served as the inspiration for Dylan to come up with the character in the song’s title. Their paths would cross again 8 years later, in 1973, when Langhorne put mariachi touches with his guitar on pieces such as Main Title Theme (Billy), Cantina Theme, Billy 1, and River Theme, for the soundtrack to the film Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid.

Mike Bloomfield

Mike Bloomfield was born and raised in Chicago, electric blues paradise. While just a teen he became one of the few whites who never missed a performance of Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, Otis Spann, Buddy Guy, or two of the great figures of this style, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. Before long they let him take the stage with them, being one of the lucky few to drink from the original fountain. In the mid 60s, Dylan was an absolute fan, and made him the secret piece to his electric conversion. Together they recorded Like a Rolling Stone and the rest of my personal favourite album of all time, Highway 61 Revisited. His most shining moment was on Tombstone Blues when he responds with fury, and sharp bursts on his ‘63 Telecaster to the torrent of Dylan’s words. The amazing thing is that Bloomfield, as was his habit, never used any effects, beyond the tone and volume controls, and his Tele plugged directly into an Ampeg Gemini. He’s not too bad on the slide either on the title song, for which he used a cut handle bar off a bicycle. In the middle of recording the album Dylan and Bloomfield had caused much uproar among the ‘folkies’ when they heard them at the Newport Festival with this new abrasive music, especially the frenetic version of Maggie’s Farm with Bloomfield in flamethrower mode. According to the story, they electrified one half of the crowd and electrocuted the other, which ended with booing and jeers. Four days after that Dylan left his sharply recorded response, once again with Bloomfield's beautiful arpeggios, in the scathing Positively 4th Street. Their paths would not cross for another 15 years, when in November of 1980 he took the stage with Dylan to play Like a Rolling Stone, where he dedicated 10 minutes to introducing him and singing his praises, Bloomfield was in top form in spite of his spending the 70s fighting drug addiction. Up to this very day Dylan still considers him to be the best guitarist he ever played with. Yet despite their promising reencounter, Bloomfield could’t manage to rid himself of his demons and died of an overdose shortly after, on February 15, 1981.

Charlie McCoy

Charlie McCoy was one of the most acclaimed session players in Nashville and was the bait Dylan producer Bob Johnstone used to get him there. While he was working on Highway 61, Johnstone brought in McCoy. Dylan was finishing up the recording but wasn’t happy with the electric version of Desolation Row, so he decided to try it with an acoustic. McCoy cut just 2 takes, but his ‘fillers’ on guitar were the icing on the cake which is still my favourite song by the great songwriter Bob Dylan. McCoy’s contributions didn’t end there, Dylan, awed by his talent, finally went to Nashville where they recorded Blonde On Blonde, McCoy would be used on songs like Just Like a Woman, 4th Time Around, Sad Eyed Sally Lady of the Lowlands and Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine), where he plays the the trumpet and bass at the same time. He would be the bassman contributing yet more to the career of Dylan on records like John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, and Self Portrait.

Robbie Robertson

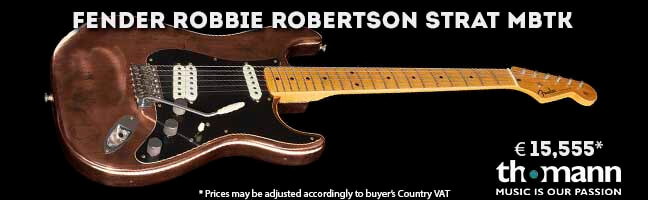

The Band’s leader is perhaps, the most significant guitar player in Dylan’s career, and he achieved the position Bloomfield rejected, Robertson led Dylan’s electric revolution with his Telecaster, being a fundamental part in the best concerts of Dylan’s life, the ones from 1966, when his smoking guitar led on tunes such as Baby Let Me Follow You Down, Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues, I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met) and that Like a Rolling Stone, when Dylan urges them to play “fucking loud” after being called Judas. He had already recorded with him on one of the best singles he ever put out on Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?, possibly the hardest and most direct rock song he ever played. Then the essential Blonde on Blonde would emerge, where you can hear Robertson’s ripping solos on Pledging My Time, Obviously Five Believers and Leopard Pill Box Hat, besides touching up such great songs as One of Us Must Know, Most Likely Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine) and Absolutely Sweet Marie. Their careers would remain tied when after Dylan had a serious bike accident in 1966, Robertson and his Hawkes were invited to his house in Woodstock, New York, and together they would revolutionise rock music again, placing the first stone in the ‘Americana’ monicker, in country/rock and in getting back to the roots with The Basement Tapes, a record that didn’t see light (legally) until 1975.

They didn’t get back together until ‘74, when Dylan came out of retirement and got back on the road after 8 years, together with the same players from then, those, who by then had their own illustrious careers, and also with some of his songs in their repertoire. Despite the fact that the tour was not nearly as good as that other one where he was jeered, this tour was an absolute success, it led them to a live album called Before The Flood, where the remake of All Along the Watchtower with Robertson unleashed really sticks out. They also recorded the new Dylan record Planet Waves, when Robertson supposedly changed his trusty Telecasters from the 50s and 60s to a red ‘54 Stratocaster.

Peter Drake

The pedal steel legend Pete Drake gave the distinct note to the new change of style in Dylan at the end of the 60s, which opened the doors to country rock with records like John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline. In the former Drake only appeared in two songs, but his mark is indelible on one of Dylan’s greatest classics, I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight. On the 2nd his print is much clearer on lovely contributions in numbers as big as Lay Lady Lay and Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You. Nevertheless, his class could not save certain mediocre work from the genius like Self Portrait or Dylan from 1973.

Mark Knopfler

Dylan had 2 revelations at the end of the 70s, the first was, none other than converting to Christianity, after according to his words, Christ had appeared before him. The second was when a mate put on the first single, Sultans of Swing, by the group called Dire Straits. Dylan decided he was going to record with that guitarist. Mark Knopfler was delighted that one of his idols wanted him and was quite surprised when he saw all the songs referred to the religious awakening of Dylan. Yet, his work was impeccable on songs like Precious Angel, a piece reminiscent of Dire Straits and Slow Train, where he uses his famous red Fender Stratocaster, and some of his other guitars including his Telecaster Custom and a Gibson ES 335. In 1983 they reunited, this time with Knopfler as co-producer, on the remarkable Infidels, his first secular record after his Christian phase. The Knopfler touch would be back on gems like Jokerman and I And I. His last studio participation to date was in 1988 on Death is Not the End from Down In the Groove.

Mick Taylor

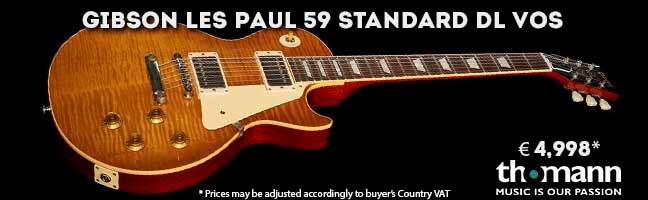

One of the most important things Knopfler did for Dylan was to bring the great Mick Taylor on board for Infidels, where the ex-Stone stuck out with his Les Paul on numbers like Sweetheart Like You, License to Kill, or showing his skill on the slide in Man of Peace and Don’t Fall Apart On Me Tonight. Dylan was so impressed with his work he took him on the tour of 1984, where he would appear on the live Real Live. The next year Taylor was back with a lovely solo in Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love), the best song on the underrated album Empire Burlesque.

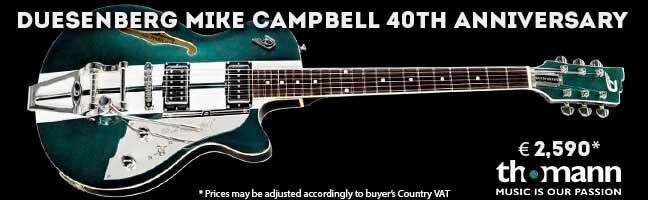

Mike Campbell

Mike Campbell has always admitted that listening to Like a Rolling Stone is what made him pick up a guitar, so it’s no surprise that one of the biggest joys of his life was the day Dylan called him to sit in on Empire Burlesque, a job where you can enjoy his guitar on songs like Seeing the Real You at Last, I’ll Remember You and his terrific solo on Emotionally Yours. But better still was the following year when Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers became Dylan’s front band. From that emerged songs like Got My Mind Made Up and Jammin’ Me, which made him one of the few to have written a song with Dylan. He reappeared on Knocked Out Loaded, check out his guitar on Maybe Someday, and in 2009 he would be his lead guitarist on Together Through Life, where he stands out on I Feel Like a Change Comin’ On and Jolene.

Daniel Lanois

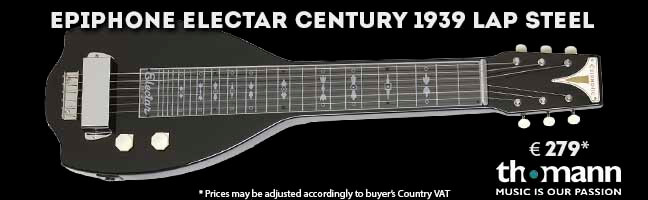

The relationship between Daniel Lanois and Bob Dylan is one of the most meaningful of the Minnesota bard’s career. It was Lanois who produced two of the albums that brought Dylan back through the big door at the end of the 80s and 90s, Oh Mercy and Time Out of Mind. When they recorded the first, in 1989, Dylan was at the lowest point of his career but together they would create the best for a long time with Desire. Lanois’ atmospheric touch and expertise on multiple string instruments were essential, playing the dobro on several songs including the solo in What Good Am I?, the guitar on numbers like Ring Them Bells, and Most of the Time, and the lap steel on Where Teardrops Fall, which brings Peter Drake to mind . Much better and much more conflictive was his part in Time Out of Mind, one of the best records of his career which led to his final reinvention. One of the ‘blessed’ problems was that Dylan turned up with his guitarist Duke Robillard, and Lanois didn’t take it very well. But in the end, the result was explosive with all three guitars mixed into the moods of Lanois, who even could show off with a solo on his ‘56 Gibson Les Paul Gold Top on the rockabilly Dirt Road Blues.

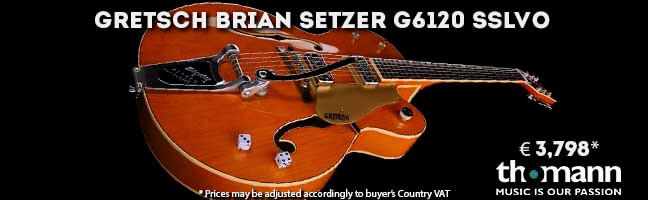

Charlie Sexton

Charlie Sexton’s entrance, along with Larry Campbell into Dylan’s band gave him one of the best pair of guitarists he had ever had. Together with this excellent band they would record some of the finest things in his career like Things Have Changed, a song that would win him an Oscar, and the outstanding Love & Theft, his last masterpiece to date. On this album Sexton is impressive on songs like Summer Days, a rockabilly that Brian Setzer could have penned, where Sexton glows, his slide is preeminent on Honest With Me and his interaction with Campbell is almost telepathic on Po Boy. In 2002 he left the group only to return in 2009, cut the remarkable Tempest in 2012, with an amazing solo in Scarlet Town, and the trilogy of ‘standards’ that make up Shadows In The Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016) and Triplicate (2017) on which he plays his Collings SoCo Deluxe.